Zia refused Bangabandhu murder probe body’s entry

The British jurists of the first Commission of Enquiry into the murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and the national four leaders could not come to Bangladesh in January 1981 to investigate the gruesome killings of 1975.

General Ziaur Rahman’s government did not issue visas to them, according to the preliminary report of the Commission set up on 18 September 1980 in London.

“In the absence of evidence that the law had been allowed to take its course the Commission of Enquiry decided that one of its members should visit Bangladesh to enquire into the position and, application for a visa for Mr Jeffrey Thomas, Q.C, MP, and an assistant to visit Bangladesh in January 1981 was made to the High Commission in London,” according to the report.

“That visit could not take place as visas were not issued for Mr Thomas and his assistant, no letter of refusal was ever sent to the Commission or its Secretary, and, despite a number of letters and requests to the High Commission, no letter have ever been received from the High Commission in relation to the proposed visit.”

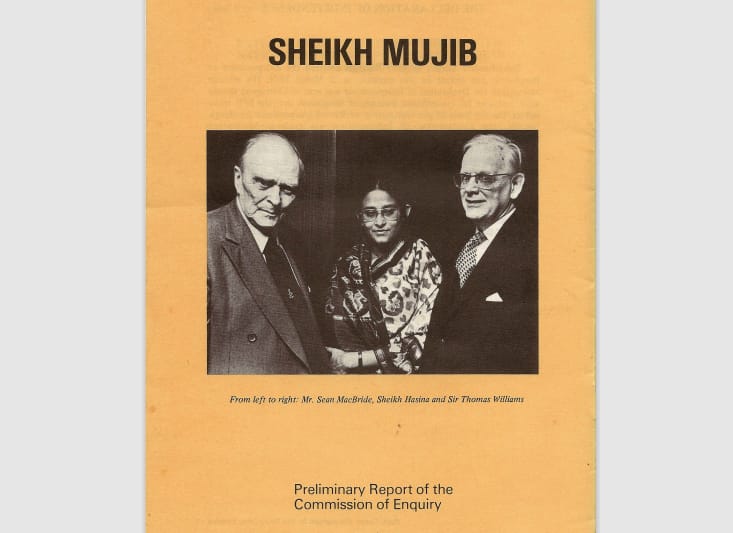

Sir Thomas Williams, Q.C, MP, was the head of the Commission while Sean MacBride, S.C, former president of Amnesty International and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Jeffrey Thomas, Q.C, MP, and Aubrey Rose were the other members.

General Ziaur Rahman, the founder of the BNP, was the president in Bangladesh during that time.

Father of the nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was killed along with most of his family members on Aug 15 of 1975 when he was the President of Bangladesh.

His two daughters - Sheikh Hasina, now prime minister, and Sheikh Rehana – luckily survived as they were in Europe at that time.

Four national leaders -- Syed Nazrul Islam, Vice-president, Tajuddin Ahmed, first Prime Minister, M Mansur Ali, Prime Minister, and AHM Qamaruzzaman, Industries Minister– were shot dead during detention inside Dhaka Central Jail on Nov 3, 1975.

Following those murders, an indemnity ordinance was issued giving the legal immunity to the killers. Twelve army officers who were involved in the assassination had been rewarded with jobs in diplomatic missions abroad in 1977 when Ziaur Rahman came to power through a military coup.

The trial process of Bangabandhu's murder started 21 years after the gruesome carnage, when the Awami League was elected to power in 1996.

After a lengthy trial, the court convicted 12 suspects and awarded them the death penalty in 2010.

Four of them are still absconding with M Rashed Chowdhury living in the US and AHMB Noor Chowdhury in Canada. The whereabouts of Abdur Rashid and Shariful Haque Dalim are still not clear. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina earlier said both of them were in Pakistan.

The Commission of Enquiry was set up with the purpose of enquiring why the process of law and justice had not taken place after those murders.

The preliminary conclusions reached by the Commission were 1.The process of law and justice has not been permitted to take their course. 2. It would appear that the government had duly been responsible for impeding their process. 3. These impediments should be removed and law and justice should be allowed to take their course.

Members of the Commission had at their disposal a large number of papers relating to affairs in Bangladesh, public statements and documents, the report of Amnesty International following their mission to Bangladesh in 1977 and other documents to enable them to ascertain the facts.

According to the preliminary report, the initiative to constitute this Commission was taken by Sir Thomas Williams in response to an appeal made by Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, surviving daughters of Bangabandhu, and by M. Selim and Sayed Ashraf-ul-Islam, sons of murdered Prime Minister and Vice-President.

This appeal had been widely supported in public meetings held in Bangladesh as well as abroad. The first meeting of the Commission was held in one of the Committee Rooms of the House of Commons on 18 September, 1980, under the Chairmanship of Sir Thomas Williams.

Sheikh Hasina’s Foreword

Sheikh Hasina wrote the foreword of the preliminary report.

She wrote “My father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, members of our family, and four of my father’s closest political associates were assassinated on 15 August and 3 November, 1975 respectively.

“Sheikh Mujib was the founding father of Bangladesh Republic and both he and his colleagues were the democratically elected representatives of their people. They stood for secular democratic Bangladesh and it was the purpose of their murderers and fellow conspirators to defeat these ends and create a sectarian society.

“Their deaths, which were part of a coup, signaled the end of democracy in the infant state and marked the beginning of military rule. The assassination was obviously part of a wider conspiracy involving leading figures in the country’s military and political establishment.

“Thus, despite repeated promises by the Dacca regime, none of the murderers have been brought to book. Indeed, they and their fellow conspirators have, during these intervening years, enjoyed the protection and patronage of the government. Some of them have been appointed to diplomatic missions abroad, while others occupy positions of privilege at home. In this instance crime has paid.

“Unable to get satisfaction from the Bangladesh authorities, the families of the victims and their democratic minded supporters in Britain, determined that the matter must not be allowed to rest, persuaded a number of distinguished jurists to set up a commission to inquire into the murder of Bangabandhu and his family and of the four national leaders while under detention without trial in the Dacca Central Jail.

“Their names and reputations are a guarantee that the inquiry will conform to the highest standards of judicial propriety.

“Their findings will, we hope, arouse the world’s conscience to these acts of terror and to the abuses of the rule of law that have disfigured the political and social life of Bangladesh these past seven years.

“It is the right and duty of governments and peoples, who cherish democratic values, to support the democratic rights of peoples in all parts of the world. And when such norms are violated, they should express their abhorrence in every manner open to them.

“The Dacca junta is critically dependent on the largess of foreign governments and peoples. International opinion can, therefore, play an important part in helping to bring the murderers to trial as a first step towards restoration of the rule of law and democratic life in Bangladesh,” she wrote on November 3 in 1982 from London from where the report was published.