The twisted tale of Lars von Trier

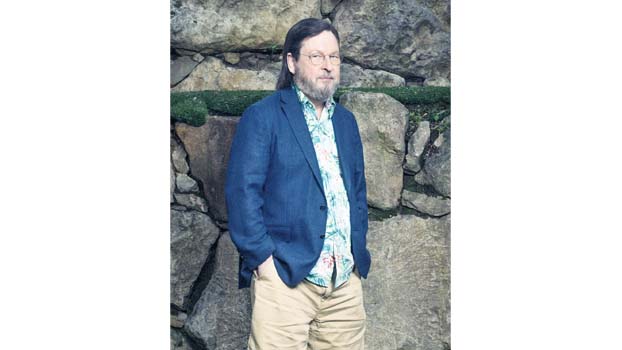

Lars von Trier original name Lars Trier, born in 30 April 1956 is a Danish film director and screenwriter with a prolific and controversial career spanning almost four decades. His work is known for its genre and technical innovation; confrontational examination of existential, social, and political issues; and his treatment of subjects such as mercy, sacrifice, and mental health.

Von Trier was born in Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, north of Copenhagen, to Inger Høst and Fritz Michael Hartmann (the head of Denmark's Ministry of Social Affairs and a World War II resistance fighter). He received his surname from Høst's husband, Ulf Trier, whom he believed was his biological father until 1989.

He later added the aristocratic "von" to his name for aristocratic effect) and raised by his radical, nudist Communist parents in an unconventional environment where, as the director once put it, everything was permitted except "feelings, religion and enjoyment," the young man blossomed into a neurotic, left-wing, movie-loving youth. Given a Super-8 camera at age 11, von Trier spent his teens making movies and entered Copenhagen's film school in the early '80s.

He studied film theory at the University of Copenhagen and film direction at the National Film School of Denmark. At 25, he won two Best School Film awards at the Munich International Festival of Film Schools for Nocturne and Last Detail. The same year, he added the German nobiliary particle "von" to his name, possibly as a satirical homage to the equally self-invented titles of directors Erich von Stroheim and Josef von Sternberg, and saw his graduation film Images of Liberation released as a theatrical feature.

Von Trier began his career with the crime film ‘Forbrydelsens element’ (1984; The Element of Crime), the first in an eventual series known as the Europa trilogy, which stylishly explores chaos and alienation in modern Europe. The other films in the trilogy are ‘Epidemic’ (1987), a metafictional allegory about a plague, and ‘Europa’ (1991; released in the US as Zentropa), an examination of life in post-World War II Germany. In 1994 von Trier wrote and directed a Danish television miniseries called ‘Riget’ (The Kingdom), which was set in a hospital and focused on the supernatural and macabre. It proved so popular that it was followed by a sequel, ‘Riget II’ (1997), and later inspired an American version, adapted by American horror novelist Stephen King, for which von Trier served as executive producer.

In 1995 von Trier and Danish director Thomas Vinterberg wrote a manifesto for a purist film movement called ‘Dogme 95’. Participating directors took what the group dubbed the Vow of Chastity, which bound them to a list of tenets that, among other things, forbade the use of any props or effects not natural to the film’s setting in order to achieve a straightforward form of narrative-based realism. Von Trier’s next film was ‘Breaking the Waves’ (1996), a grim tale about a pious Scottish woman subjected to brutality that was anchored by a bravura Oscar-nominated performance by Emily Watson. It embodies much of the spirit of Dogme 95, though it was not technically certified as such. In the end, the only official Dogme 95 film that von Trier directed was ‘Idioterne’ (1998; The Idiots), a highly controversial work that centres on a group of people who publicly pretend to be developmentally disabled.

In 2000 von Trier released Dancer in the Dark, a melodrama that features Icelandic pop singer Björk as a nearly blind factory worker who finds relief from her constant travails in fantasy-fueled musical numbers. Von Trier attracted further attention for ‘Dogville’ (2003), a cynical and dramatically austere parable about the United States, starring Nicole Kidman. Though it was criticized for its lack of subtlety and for its gender politics, the film was followed two years later by a sequel, ‘Manderlay’. Later films included ‘Antichrist’ (2009), which agitated audiences with its graphic depiction of sexual violence within a grieving couple’s relationship, and the haunting ‘Melancholia’ (2011), in which a chaotic wedding and attendant familial discord are set against a planet’s impending collision with Earth. His next film, ‘Nymphomaniac’, was released in two volumes (2013). It chronicled the carnal activities of a single woman—played by several actresses at different ages—from her first experiences to her later assignations. The film was highly controversial because of its depiction of unsimulated sex acts. He next directed ‘The House That Jack Built’ (2018), a deliberately provocative film that follows a serial killer through a succession of murders.

Von Trier’s subversive deployment of genre and cinematic cliché is ably explored in Honig and Marso’s Introduction, ‘Lars von Trier and the “Clichés of our Times”’. Reversing some of the media clichés about von Trier, they argue that his fascination with cliché provides the subject matter and target of his films. Indeed, intensifying clichés of gender, power, and politics in a manner that ironises them, they claim, ‘may press democratic and feminist theory in new directions’, perhaps liberating theorists from their own ennui. Von Trier’s extraction of the ‘truth’ in clichés dealing with anti-Semitism, race relations, gender politics, and misogyny reveals him to be a ‘thinker in cinema’ (to use Thomas Elsaesser’s phrase) whose cinematic provocations contest the ideological clichés of our age.

These two pieces are followed by a recent Danish interview with von Trier, where he explains his fascination with Judaism and shock at discovering, at his mother’s deathbed, that his father was not Jewish but German. This interview is framed by video artist Tony Cokes’ images of text fragments from von Trier’s notorious ‘Nazi’ interview at Cannes (with later sections on David Bowie and Kanye West). The interdisciplinary credentials of the volume thus established, the chapters then track the best known films of von Trier’s oeuvre, with essays on The Element of Crime (1984), Europa (1991), Breaking the Waves (1996), The Idiots (1998), Dancer in the Dark (2000), Dogville (2003), Manderlay (2005), Antichrist (2009), Melancholia (2011), and Nymphomaniac Volumes I and II (2013). Despite Panagia’s claims to present a novel integration of political and cinematic analyses, the chapters fall into two camps: those that explore various aesthetic aspects of von Trier’s work and those that focus on more explicitly ethical or political themes or topics.

Turning his terror of hospitals into superb entertainment, von Trier mounted the chilling miniseries ‘The Kingdom’ (1994) for Danish TV. Shot on location in a Copenhagen hospital in 16 mm with available light, The Kingdom was an inspired blend of Twin Peaks freakiness with ER procedural kineticism in its story of a haunted hospital. A TV and film festival hit, The Kingdom also became a precursor to the new aesthetic and spiritual concerns of von Trier's subsequent 1990s feature films. Embroiled in personal turmoil mid-decade, including his mother's 1995 deathbed revelation of his actual biological father (who wanted nothing to do with von Trier after an initial meeting), von Trier definitively rebelled against his past. Along with converting to Catholicism, von Trier broke from the perfectionist style of his Europe trilogy, aiming to achieve the "honesty" he admired in Danish iconoclast Carl Theodore Dreyer's work with his own self-imposed artistic "chastity".

His film ‘The House That Jack Built’ that premiered out of competition at Cannes—“vomitive” and “pathetic” are some of the adjectives being used by filmgoers to describe it. In a surprising turnabout, von Trier was welcomed back to Cannes after being proclaimed “persona non grata” for a joke in poor taste, mistakenly interpreted as pro-Nazi by the festival in 2011.

Von Trier periodically suffers from depression, and also from various fears and phobias, including an intense fear of flying. This fear frequently places severe constraints on him and his crew, necessitating that virtually all of his films be shot in either Denmark or Sweden. As he quipped in an interview, "Basically, I'm afraid of everything in life, except film making."

On numerous occasions, von Trier has also stated that he suffers from occasional depression which renders him incapable of performing his work and unable to fulfill social obligations.