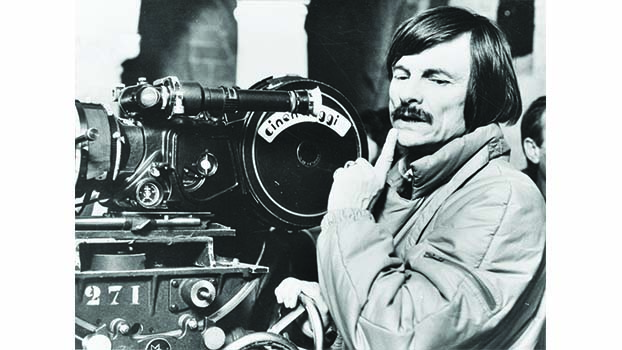

The Tarkovsky legacy

Art & Glamour Desk

Andrei Tarkovsky was the most spiritual and poetic director of all time. For him cinematography was not entertainment, it was art in the best meaning of this word. He was one of the most educated directors – he studied music and painting, he was born into the family of a poet. Being a versatile artist he was able to create a synthesis of arts in his films. Film for him was not just a reflection of reality; it was more like a poem or a dream.

The most famous Soviet film-maker since Sergei M. Eisenstein, Andrei Tarkovsky (the son of noted poet Arseniy Tarkovsky) was born on 4 April 1932 in Yuryevetsky District, Russia. In his school years, Tarkovsky was a troublemaker and a poor student. He still managed to graduate, and from 1951 to 1952 studied Arabic at the Oriental Institute in Moscow, a branch of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Although he already spoke some Arabic and was a successful student in his first semesters, he did not finish his studies and dropped out to work as a prospector for the Academy of Science Institute for Non-Ferrous Metals and Gold. He participated in a year-long research expedition to the river Kureikye near Turukhansk in the Krasnoyarsk Province. During this time in the taiga, Tarkovsky decided to study film and got enrolled in the Soviet film school State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) and was admitted to the film-directing program. He was in the same class as Irma Raush whom he married in April 1957.

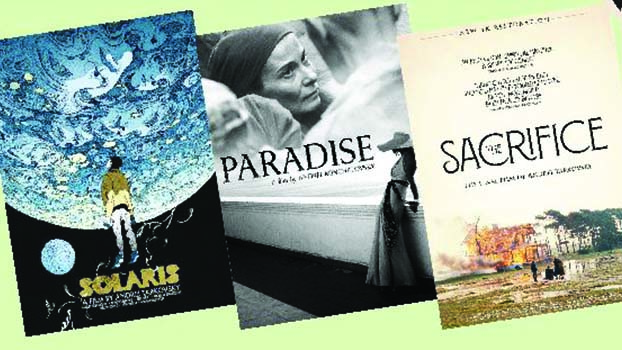

He shot to international attention with his first feature, ‘Ivan's Childhood’ (1962), which won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival. This resulted in high expectations for his second feature, ‘Andrei Rublyov’ (1969), which was banned by the Soviet authorities until 1971. It was shown at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival at four o'clock in the morning on the last day, in order to prevent it from winning a prize - but it won one nonetheless, and was eventually distributed abroad partly to enable the authorities to save face. ‘Solaris’ (1972), had an easier ride, being acclaimed by many in Europe and North America as the Soviet answer to Kubrick's '2001' (though Tarkovsky himself was never too fond of it), but he ran into official trouble again with ‘The Mirror’ (1975), a dense, personal web of autobiographical memories with a radically innovative plot structure. ‘Stalker’ (1979) had to be completely reshot on a dramatically reduced budget after an accident in the laboratory destroyed the first version, and after ‘Nostalgia’ (1983), shot in Italy (with official approval), Tarkovsky defected to Europe.

The early Khrushchev era offered good opportunities for young film directors. Before 1953, annual film production was low and most films were directed by veteran directors. After 1953, more films were produced, many of them by young directors. The Khrushchev Thaw relaxed Soviet social restrictions a bit and permitted a limited influx of European and North American literature, films and music. This allowed Tarkovsky to see films of the Italian neorealists, French New Wave, and of directors such as Kurosawa, Buñuel, Bergman, Bresson, Andrzej Wajda (whose film Ashes and Diamonds influenced Tarkovsky) and Mizoguchi.

Tarkovsky's teacher and mentor was Mikhail Romm, who taught many film students who would later become influential film directors. In 1956 Tarkovsky directed his first student short film, ‘The Killers’, from a short story of Ernest Hemingway. The short film ‘There Will Be No Leave Today’ and the screenplay ‘Concentrate’ followed in 1958 and 1959.

An important influence on Tarkovsky was the film director Grigori Chukhrai, who was teaching at the VGIK. Impressed by the talent of his student, Chukhrai offered Tarkovsky a position as assistant director for his film Clear Skies. Tarkovsky initially showed interest but then decided to concentrate on his studies and his own projects.

During his third year at the VGIK, Tarkovsky met Andrei Konchalovsky. They found much in common as they liked the same film directors and shared ideas on cinema and films. In 1959 they wrote the script ‘Antarctica – Distant Country’, which was later published in the Moskovskij Komsomolets. Tarkovsky submitted the script to Lenfilm, but it was rejected. They were more successful with the script The Steamroller and the Violin, which they sold to Mosfilm. This became Tarkovsky's graduation project, earning him his diploma in 1960 and winning First Prize at the New York Student Film Festival in 1961.

Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky is widely regarded as one of cinema’s true masters. Sight & Sound’s 2012 poll of the best films of all time saw no less than three of his movies – ‘Mirror’ (1974), ‘Andrei Rublev’ (1966), and ‘Stalker’ (1979) – voted into the top 30 by critics and directors.

Ingmar Bergman once said, “Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all. He moves with such naturalness in the room of dreams. He doesn’t explain. What should he explain anyhow?”

The reverence Tarkovsky inspires and the oblique, sombre and high-minded nature of his work have been a turn-off for some. His small output was the result of relentless obstruction from the Soviet authorities, who viewed his films as elitist. But he refused to compromise his vision. Letting go of an urge to figure out a concrete meaning, audiences open themselves up to the rhythms of his slow, long takes (he famously described filmmaking as “sculpting in time”) and the mysterious magic of imagery which is hard to match for sheer beauty.

A poetic sense for the dreamlike hold of memory and the elemental grandeur of nature already shines through Tarkovsky’s first feature Ivan’s Childhood (1962), within the more conventional, suspenseful format of a Soviet war movie about a 12-year-old on reconnaissance at the front. But for a sense of the director’s fully-developed vision, Stalker is perhaps the best entry point. Based on sci-fi novel The Roadside Picnic by the Strugatsky brothers, it still has a relatively straightforward plot, but is dense with enigmatic philosophy over its unhurried, meditative 160 minutes. As in all Tarkovsky’s work, spiritual crisis is the theme. But wry dialogue punctuates its melancholy, defying those who claim he doesn’t have a sense of humour.

An outlaw guide, or ‘Stalker’, leads a writer and professor on an expedition into the zone, a treacherous area of overgrown, strangely sentient land which has been cordoned off by the government. In an iconic sequence they travel into its heart on a railway car, its wheel-clanking hypnotically blending with a sparse electronic score. Their destination is a Room said to have the power to fulfil one’s innermost desire. Their quest and differing worldviews are shadowed by the story of another Stalker who hanged himself after becoming fabulously wealthy, the Room having revealed the truth of his nature.

Tarkovsky saw true artists as prophets with a gift of prescience. The evocative power of Stalker, shot close to a toxic chemical plant near Tallinn, is enhanced by its uncanny prefiguring of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster seven years later and its irradiated, ghostly exclusion zone. His fifth feature, it is the last he made in the Soviet Union.

Tarkovsky’s other sci-fi adaptation was ‘Solaris’ (1972), based on the novel by Stanislaw Lem. It’s set in outer space, but is also more focused more on the story’s psychological and emotional resonances, making it an eerie meditation on the persistence of memory. An oceanic, sentient planet’s proximity is causing strange phenomena among the crew on a space station. When Kris (Donatas Banionis) goes to investigate, he is confronted with visitations from his late wife Hari (Natal’ya Bondarchuk), who committed suicide.

‘Mirror’ is arguably Tarkovsky’s greatest masterpiece. It’s also his most unconventional in form. Autobiographical and highly personal, it unfolds with the associa

tive logic of a dream. Fragments of memory from his childhood are woven in with narration of his father Arseny’s poems, on time and immortality. Devastating archival footage of Red Army troops arduously trudging through mud allows these recollections to reverberate within Russia’s tumultuous national history.

An iconic dream sequence of the mother levitating above a bed as water cascades indoors is one of cinema’s most sublime, and epitomises Tarkovsky’s recurrent use of rain, fire and supernatural imagery to create an oneiric universe teeming with life’s mysterious forces. He said that only after making this film did he stop dreaming about the house he had once lived in.

Tarkovsky’s other work of exile was his haunting, supernatural-tinged last film ‘The Sacrifice’ (1986), shot on the Swedish island of Gotland, and not in his native language. It looks at times like a Bergman film – not surprising given he enlisted Bergman’s brilliant cinematographer Sven Nykvist and won an almost unprecedented four prizes at the Cannes Film Festival.

Tarkovsky died shortly after its completion, and his lung cancer no doubt fed into its apocalyptic themes. In it, a family gathers to celebrate the birthday of disillusioned intellectual, Alexander. As World War III breaks out bringing the threat of nuclear annihilation, he tries to strike a bargain with God. It’s a fitting contemplation on how much a man must give up personally to nourish a greater life force.