The risks of de-banking in the Pacific

As access to international banks declines across the Pacific, Nauru’s domestic and cross-border banking services are hanging by a thread. There is a real possibility that Nauru will have no cross-border banking services as soon as mid-2025.

Australia’s Bendigo Bank is the only provider of banking services in Nauru. In late November 2023, Bendigo Bank announced that it would close its agency in Nauru in December 2024. But after the Chinese state-owned Bank of China reportedly signalled its interest in March 2024 to fill the gap left by the closure and set up a branch, Bendigo Bank announced its withdrawal will be delayed until June 2025.

With a population of less than 13,000, Nauru is one of several small countries that risk losing access to the global financial system. Cross-border banking requires domestic banks to have correspondent banking relationships with international counterparts. Across the globe, correspondent banking relationships have declined — a trend pronounced in relation to smaller developing economies.

Pacific island nations have been especially hard-hit with many now relying on a single or a handful of correspondent relationships. In some cases, the costs of these services increased while their scope declined. The loss of Bendigo Bank will sever Nauru’s connectivity to the global financial system while terminating commercial banking and payment services domestically.

The closure of Nauru’s only commercial bank operation will force employers to pay their employees in cash.

Cash payments will need to be made for goods, services and even to settle taxes. Cross-border trade settlement will be even more complicated. Payments may need to be made offshore through other institutions that can provide electronic payment services, such as formal remittance providers.

These complications are not unfamiliar to Nauru. For more than a decade until Bendigo Bank established its agency in June 2015, no commercial banking services were available in the country. Even with Bendigo Bank, access to financial services was limited as Bendigo Bank’s foreign correspondents restricted the services provided in Nauru. Conditions imposed by US correspondent banks inform many de-banking decisions by Australian banks.

There are several reasons that banks may be reluctant to extend services to Nauru. Sprawling geography and small economies make it difficult to turn a profit in remote island nations. Anti-money laundering laws increase the banking challenge. These laws require banks to mitigate money laundering, and terrorism and proliferation financing risks.

Though the Pacific region has one of the lowest crime rates globally, it is increasingly used as a drug transit route for the Australian and New Zealand markets. That, in turn, has led to an increase in local drug supply and use. Foreign banks also cite corruption risks. But it is uncertain to what extent proceeds of such offences pose a risk to domestic and cross-border banking services. The main proceeds of drug trafficking would be generated in other markets and significant corruption payments are often made and managed offshore.

Nauru unfortunately has a bad history with money laundering. In the late 1990s, Nauru was a tax haven that facilitated the laundering of more than US$70 billion (equivalent to US$134.8 billion in 2024) by Russian criminals and was involved in the Bank of New York scandal. Nauru was subsequently blacklisted by the Financial Action Task Force — the global standard-setting body combating money laundering, and terrorism and proliferation financing.

Though Nauru’s offshore banking sector was shut down in 2003, this history is still cited by international bank compliance officers as an indicator of current higher money laundering risks in Nauru and the Pacific.

As risk management concerns loom large in de-banking decisions, they are generally classified as institutional ‘de-risking’ decisions, informed by financial and reputational risk and the cost of bank risk management. Ironically, the ‘de-risking’ of large banks shifts the risks elsewhere — often to smaller institutions that have less capacity to mitigate those risks, or into the cash economy. Such displacement complicates law enforcement efforts and tends to increase national crime risk levels. But for the first time in years, there is reason to be optimistic that the Pacific is turning the de-banking corner.

Upon the request of the Pacific Island Forum, the World Bank studied the correspondent banking decline in the Pacific and made recommendations to improve international banking resilience in the region. The report and its recommendations were adopted by the Pacific Island Forum Economic and Finance ministers in August 2023. A subsequent roadmap to implement the recommendations was adopted in March 2024.

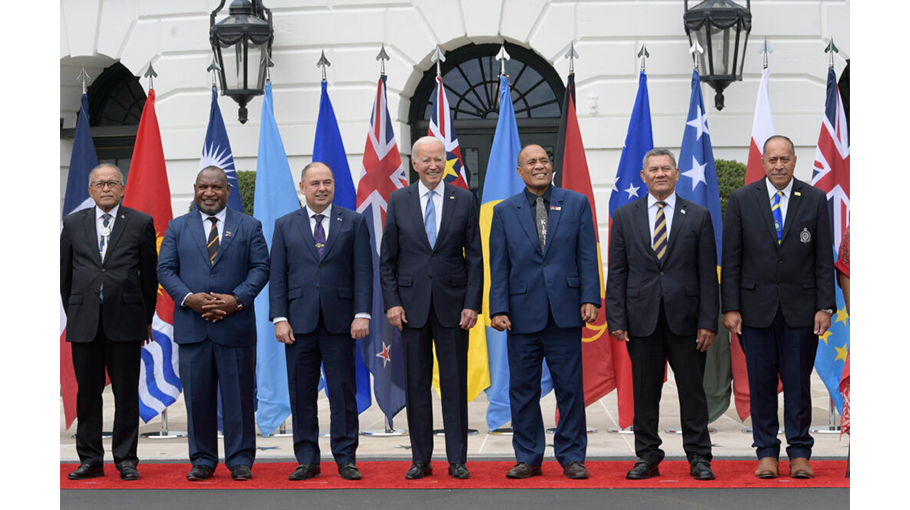

In conjunction with this work, US President Joe Biden and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, in consultation with Pacific countries, launched the Pacific Banking Forum to address de-risking and ensure technical assistance to improve the region’s access to financial services. The Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat also signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Correspondent Banking Relationships with the US Department of the Treasury to support dialogue.

The combination of the roadmap, political support, technical assistance and collaboration with the banking sector may create the right conditions to stabilise and improve access to cross-border banking services in the Pacific region. Additional development assistance, subsidies, regulatory and supervisory support and improved Pacific risk data to inform fair bank risk assessments and risk mitigation may be required to ensure the delivery of services to the smallest nations in the Pacific, including Nauru.

Louis de Koker is Professor of Law at La Trobe Law School, La Trobe University.

Source: East Asia Forum