The long game in Singapore’s ‘next gen’ politics

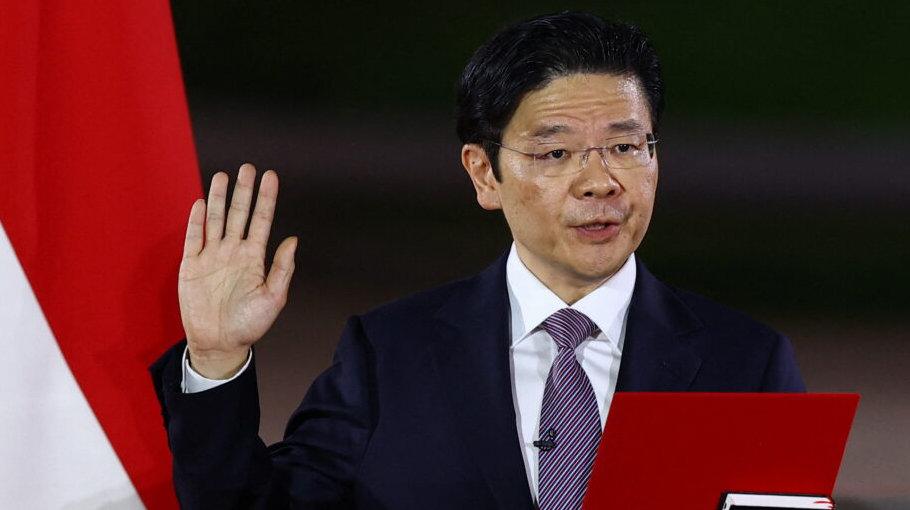

Singapore’s new prime minister Lawrence Wong, a 51-year-old technocrat with close ties to former premier Lee Hsien Loong, has settled into office after his elevation in May 2024. Wong’s ascent marks just the third transition since the country’s independence in 1965 and continues the uninterrupted rule of the People’s Action Party (PAP).

The novelty of this transition drove extensive commentary and public interest. A common theme throughout is the difficulty of the task that confronts Wong. That begins with evolving geopolitical challenges, particularly the uncomfortable squeeze that the emerging great power rivalry places on smaller states like Singapore. It also includes myriad domestic issues, including discontent with a rising cost of living, anxieties over immigration and political difficulties within the PAP, which some see as creating ‘cracks’ in Singapore’s ‘heavily state-directed society’.

These challenges are real and undoubtedly require careful attention. But they may not be as novel as implied. As a small city-state, Singapore has always faced a degree of geopolitical precarity, which it has repeatedly proven adept at navigating. On the domestic front, bread-and-butter themes, immigration and even rising demands for greater political space have been part of the political discourse for at least the past decade. These challenges have not turned Singaporean politics on its head.

In the near term, that may well make the commentary surrounding Wong’s prospects much ado about nothing. The PAP’s model of governing is both well institutionalised and resilient. Continuity in the cabinet, which Wong has pledged to maintain at least until the next general election, will provide him space to gradually settle into the role. Those factors leave little reason to expect any dramatic shifts on the immediate horizon.

But in Singapore, politics are rarely about the immediate horizon. The PAP’s dominance has allowed the party’s leadership to think less in terms of renewed mandates every few years — as counterparts in more competitive democracies often must do — and more in terms of decades. And over this extended horizon, Wong and his cohort of fourth-generation leaders face a challenge quite distinct from those that confronted their predecessors.

That challenge has to do with the very model of governing that they have adopted from their PAP elders. The PAP has long prided itself on eschewing ideologies in favour of a pragmatic and

results-oriented approach to politics. In practice, that meant emphasising the quality of its candidates and their ability to make difficult decisions.

The model’s utility was justified by the results it produced in such broad areas as growth, development and stability. By contrast, coherent and differentiated policy platforms mattered little. Over decades, large swathes of the electorate came to approach politics through this lens as well, limiting the appeal of alternative approaches.

Therein lies the challenge. This model of governing remains viable only so long as it can continue to deliver results. Whatever Wong’s abilities, that task is harder today than ever before — having become one of the world’s richest countries, additional gains will necessarily be smaller in scale than they were at earlier stages of development. That basic logic extends throughout wide areas of the public domain as well. Having been conditioned to expect an efficient government and world-leading infrastructure, even modest shortfalls elicit sharply critical public reactions.

For the PAP, the squeeze from diminishing returns is compounded by the evolving challenge from opposition parties.

The PAP’s extensive recruitment advantages have long allowed their candidates to distinguish themselves in terms of valence considerations such as credentials and governing record. This compelled the opposition to contest on policy and ideological positions that did not sufficiently resonate with the electorate to secure majorities at the ballot box.

That is no longer obviously true. Two opposition parties in particular — the Workers’ Party and the Progress Singapore Party — have recruited competent candidates that have successfully challenged PAP candidates on valence considerations, effectively ending the PAP’s monopoly on party credibility.

Ultimately, Wong does face considerable geopolitical and domestic challenges, as do all leaders of smaller and middle-sized countries. But his greater challenge comes in assuming power at a stage of Singapore’s development where the furious growth that has long fuelled its model of politics simply cannot be maintained.

The PAP is unlikely to lose an election in the foreseeable future, but in any case, the stakes go well beyond partisan considerations — if the goalposts remain unchanged and no party is able to deliver gains at a pace that satisfies the electorate, the legitimacy of the system itself will increasingly erode.

The task is to reimagine the objectives of governing. Growth and development will invariably remain part of the equation, but their long-standing primacy has run its course. That begs the question of what will take their place.

Singapore’s uniqueness as a small city-state means there are no off-the-shelf models to adopt. In any case, offering ideas that broaden the definition of success, as Wong has begun via the Forward Singapore exercise, is relatively easy. Implementing them and convincing the electorate to embrace those new goalposts is not.

Fortunately for Wong, there is no more commanding platform in Singaporean politics than the office he now occupies.

Kai Ostwald is the HSBC Chair in Asian Research and Associate Professor in the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia. He is also Director of UBC’s Institute of Asian Research.

Source: East Asia Forum