The case for ‘hibernating’ during winter

As the days shorten and the dark hours stretch, every impulse in me is to slow down, get under a blanket and stay there till spring. In a 2020 piece for The Atlantic exploring the possibility of human hibernation, James Hamblin wrote that as the winter months come upon us, “Maybe our minds and bodies are telling us we’re not supposed to be fighting so hard.” As the New York winter hardened, he resolved: “It is absolutely ridiculous that we don’t hibernate.” Hamblin makes clear that we can’t actually hibernate all winter long, though short periods of human hibernation are theoretically possible and could be useful for certain medical treatments. Still, his basic point is spot on.

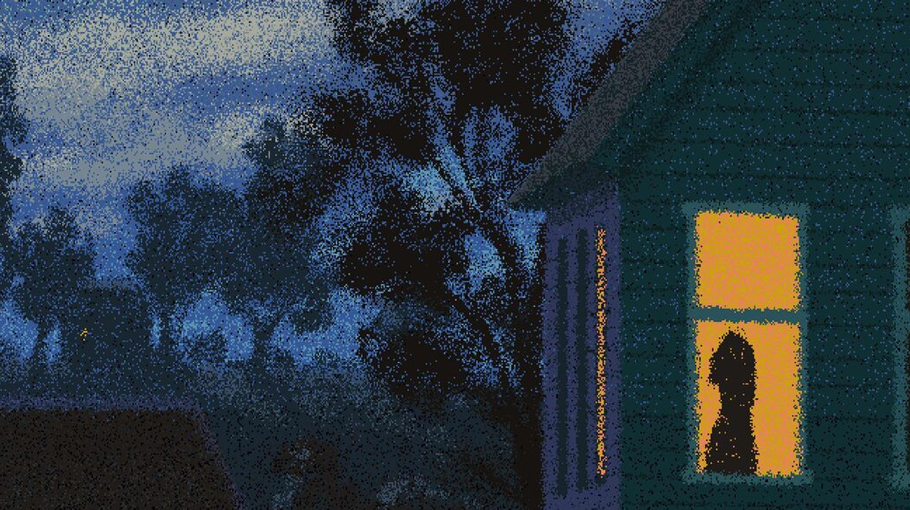

Our urge to decelerate around late autumn and throughout winter ought to be heeded. The instinct to rest more in that quiet space of time between when the last leaves fall and the first fireflies arrive resonates with ancient human and biological rhythms. We should listen to it.

A 2020 survey by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine showed that 34 percent of US adults report sleeping more in winter. Still, according to the C.D.C., a third of US adults are not getting enough sleep. To be sure, some people have medical conditions that keep them from sleeping. But most of us could get more sleep, and know we should get more sleep, but still stay up longer to squeeze some more doomscrolling, work or entertainment into the day. Lack of sleep is linked to increased rates of heart disease, Type 2 diabetes and obesity. It also makes us angrier, more unhappy and less capable of creative, compassionate and intelligent thought. America’s sleeplessness is likely making outrage culture, political polarization and general incivility worse.

Our cultural resistance to sleep reveals a disordered relationship with our bodies and our human limitations. Arianna Huffington has lamented that in the professional world, “sleep is somehow a sign of weakness and that burnout and sleep deprivation are macho signs of strength.” This seasonal nudge to rest, then, isn’t only a physical need; it is an invitation to a spiritual practice, a better way of understanding ourselves and our place in the world. Sleep is portrayed in the Christian tradition as a grace and even an act of worship.

The theologian James Bryan Smith wrote that “the number one enemy” of “spiritual formation today is exhaustion.” He also names sleep as “the perfect example” of the relationship between discipline and grace. “You cannot force your body to sleep. Sleep is an act of surrender,” he said. “It is admitting that we are not God (who never sleeps) and that is good news. We cannot make ourselves sleep, but we can create the conditions necessary for sleep.”

To sleep, we must yield to our limitations. We are needy and fragile, yet we can rest because it is not by our own efforts, abilities or successes that we keep ourselves, our lives or the world intact.

The instinct to rest more in that quiet space

of time between when the last leaves fall and

the first fireflies arrive resonates with ancient

human and biological rhythms. We should listen to it

So maybe we cannot hibernate all winter long, but we can give ourselves permission to crawl in bed earlier and hit the snooze button with impunity. We can also make more time to sleep during the day. With all the benefits naps offer, they should be our national winter pastime, if not added to the panoply of winter competitive sports.

“If you embrace the need to nap rather than pushing through,” writes molecular biologist John Medina in his book “Brain Rules, “your brain will work better afterwards.” He points to a NASA study that showed that a 26-minute nap reduced crew members’ lapses in awareness by 34 percent compared with non-nappers.

Another study that Medina cites showed that a 45-minute nap boosted cognitive performance for the next six hours. This is why some companies, like Google and Nike, offer sleep pods or nap rooms. But napping shouldn’t be an option only for the lucky few in select corporations. I once worked as a medical scheduler, and each day one of my co-workers could be found on his lunch break nodding off in the break room or sneaking off to his car to catch a few winks.

What if this were more commonplace and acceptable? What if our employer provided him space so he didn’t have to sleep with his head propped up against the vending machine?

Through her popular Nap Ministry and her new book, “Rest Is Resistance,” Tricia Hersey encourages people to nap as a way to push back against a compulsive work culture that births both injustice and exhaustion. “I judge success by how many naps I took in a week,” she told The Times. Helen Hale, the creative director of the Nap Ministry, said that when we intentionally embrace rest, we experience “a very real kind of withdrawal from our cultural addiction to productivity.”

Naps also hold surprising biblical significance. In one of the more famous biblical naps, Elijah is running for his life, escaping political retaliation. He despairs and gives up. He’s had it. Resentful and bitter, he prays to die, lies down and takes a nap. Only then does an angel show up and help him. He is renewed enough after napping to find the will to live and continue on his journey. (Haven’t we all been there?)

In the Gospels, before Jesus miraculously calms a storm, he first has to be woken up because he has dozed off on the boat. Here, a man who is powerful enough to stop gale-force winds with his voice still nods off after a long morning. Napping in this passage is also a theological statement. It’s a physical sign of faith. While everyone else on the boat is terrified, Jesus is slack-jawed asleep. Amid a turbulent storm, Jesus is at peace, out like a light.

Napping is not only a way to honor our bodies’ circadian rhythms — giving in to that post-lunch lull we all know so well. It can also be a powerful habit that teaches us to release our death grip on efficiency and control. Anne Lamott wrote, “Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes, including you.” This season, if you are feeling weary, do not underestimate the spiritual power of a long winter’s nap.

Tish Harrison Warren (@Tish_H_Warren) is a priest in the Anglican Church in North America and the author of “Prayer in the Night: For Those Who Work or Watch or Weep.”

Source: The New York Times