Sri Lanka may need more IMF help as blasts threaten tourism

Sri Lanka faces a likely collapse in tourism following Easter Sunday bomb attacks on churches and hotels, which would deal a severe blow to the island's economy and financial markets, and potentially force it to seek further IMF assistance, report agencies.

The International Monetary Fund extended last month a US$1.5 billion (S$2.04 billion) loan for an extra year into 2020, a key step in keeping foreign investors involved in what so far this year has been a top-performing frontier debt market.

But with growth, and therefore state revenues, now likely to slow significantly, the budget targets agreed with the IMF may have to be reviewed, and the government is expected to resist pressure for any spending cuts before elections expected later this year.

There is even a possibility that more IMF money may be needed if foreign investment falls, adding to the hard currency gap left by plunging tourism receipts.

"If growth slows a lot more and the budget deficit assumptions need to be reassessed, then they'll have to sit down and negotiate something more feasible," said Alex Holmes, Asia economist at Capital Economics.

The IMF's Sri Lanka mission chief said on Tuesday that initial financial market pressures on Sri Lanka appeared contained after the "horrific" attacks.

"Decisive policy and security measures by the authorities will be important, in particular for tourism, which accounts for 5 percent of GDP, to build on the strong performance of recent years," mission chief Manuela Goretti said in a statement.

The Sri Lankan stock index dived 2.6 per cent on Tuesday in its first day of trading after the attacks that killed more than 300 people, while the heavily-managed rupee held steady.

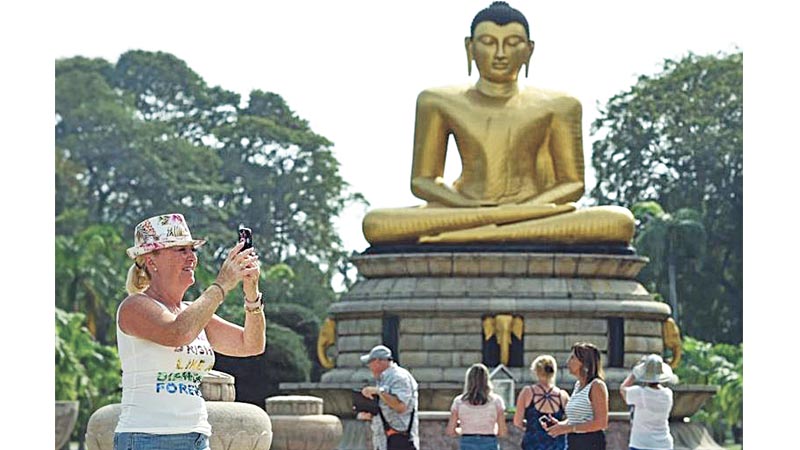

Tourism is Sri Lanka's third-largest and fastest growing source of foreign currency, after remittances and garment exports, accounting for almost US$4.4 billion of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018.

A fall in tourism receipts is bound to weaken the rupee over time. The central bank, whose coffers are too light to defend the currency through interventions, is likely to have to raise interest rates.

This, in turn, would choke lending, hurting consumers and the investment plans of local businesses, while also making it more costly for the government to seek funding from foreign investors via bond markets.

"The central bank may be forced to hike rates again this year," said Win Thin, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH).

"With foreign reserves very low right now, the central bank cannot actively support the rupee."

Read also: Tourists flee Sri Lanka, as travel industry faces uncertainty

After falling 16 per cent against the US dollar last year to record lows, the rupee had gained 4.6 per cent this year as of last week.

Sri Lankan bonds have been among the best performing globally, only bettered by Argentina and Chile. But the main stock index has lost about 10 per cent.

Weak finances

Sri Lanka's external position was already precarious.

To help fund a record US$5.9 billion in foreign loans this year, the country successfully sold US$2.4 billion in five-year and 10-year US dollar bonds last month, but that was right after the IMF extension and amid bets of looser monetary policy. In January, Sri Lanka used its reserves to repay debt worth $1 billion. It had about US$5 billion left in February, the least since April 2017, and only enough to cover two months of imports and about two-thirds of its short-term external debt, according to BBH calculations.

Colombo also needs to finance a current account deficit of about 3 percent of GDP. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe is already facing heavy criticism domestically for higher taxes, and tight monetary and fiscal policies that have crimped growth to a 17-year low.

Having emerged from a 51-day political crisis in which President Maithripala Sirisena sacked and replaced him with pro-China former president Mahinda Rajapaksa - a decision which was later reversed - Wickremesinghe set an ambitious fiscal deficit goal of 4.4 per cent of GDP, compared with 5.3 per cent in 2018.

But he also boosted spending on state employees, pensioners and the armed forces and promised more funds for rural infrastructure, leading economists to doubt the targets. A presidential vote is expected later this year followed by a general election in 2020.

"Given the fact they have repayments coming up for sovereign bonds, it could lead to more pressure on foreign currency reserves. So, it's a near term negative for the tourism sector and also market sentiment as well," said Ruchir Desai, fund manager at Asia Frontier Capital, who co-manages the $16 million AFC Asia Frontier Fund. "Valuations are cheap, no doubt... but until they get some kind of political unity which can result in stable policy-making, we will probably remain underweight (equities) until the elections."