New year, new government for New Zealand

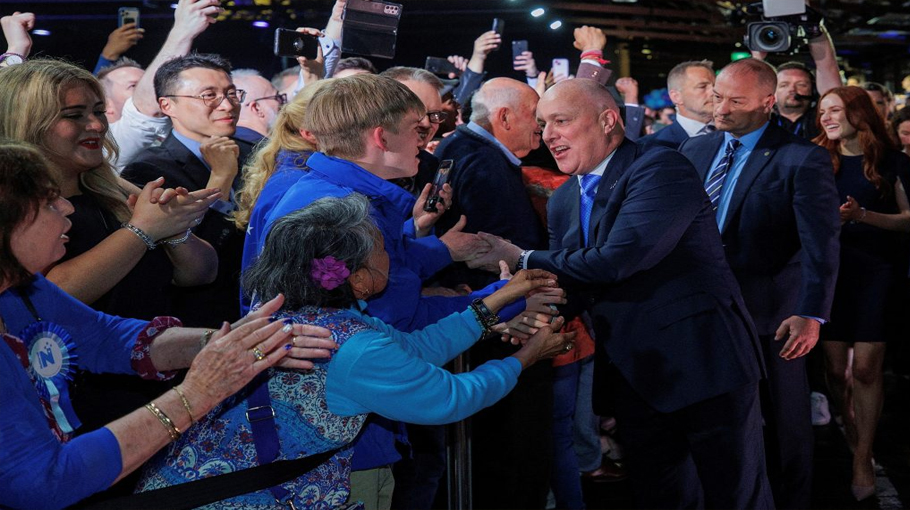

The major event in New Zealand in 2023 was undoubtedly the election and, six weeks later, the formation of a new government. Yet it remains to be seen how the new three-way coalition will, despite their differences, address issues.

It has been 30 years since New Zealand moved from a first-past-the-post electoral system to a mixed-member proportional system, in which voters determine the composition of parliament and politicians determine the executive. But the media and public debate continue as though there is still a one-step election of government.

Former prime minister Chris Hipkins’ efforts to sustain the Labour Party government after the resignation of Jacinda Ardern were unsuccessful. Too many electors shared the impression that the government had lost its ability to formulate and implement effective responses to whatever problems it recognised.

The new government is a three-way coalition between the National Party, ACT New Zealand and New Zealand First. Post-election negotiations were delayed for three weeks for the counting of special votes because it was uncertain whether the National and ACT New Zealand parties could form a majority government without the support of New Zealand First. The negotiations themselves took another three weeks and resulted in very detailed agreements between pairs of parties. They cannot be all-encompassing. The government will be judged according to how it responds to unforeseen events rather than how well it can follow blueprints.

The agreements provide for periodic review. An interparty committee meeting only once per parliamentary session cannot address all specific issues. While much will depend on individuals, especially the chiefs of staff of the parties, it is inevitable that significant issues will revert to the three party leaders. The life of cabinet ministers is likely to be fraught as decisions must now be appealing to both their own colleagues as well as the triumvirate of party leaders.

The coalition agreements established ‘ongoing decision-making principles’, including accountability, fiscal responsibility and pro-democracy. But scepticism is in order. While the coalition aims to ‘lift New Zealand’s productivity and economic growth to produce opportunities and prosperity for all New Zealanders and to conduct ‘rigorous cost benefit analysis’, there will be many trade-offs among party slogans. This has already been seen in the agreement to keep the age of eligibility for national superannuation unchanged.

Criticism of the previous government’s decisions has created a strong sense of ‘returning to the past’ in the agreements. Progressive conservatism or incremental liberalism is difficult to distinguish from blind reaction. Any broad narrative for policy design beyond ’there will be change’ remains at best implicit.

Under the new government, the Reserve Bank will again be focussed on maintaining price stability, but there is provision for ‘maximum sustainable employment’ to be managed elsewhere. Schools will be required to devote one hour each to reading, writing and mathematics every day. This policy comes as students’ performance has deteriorated significantly. But there are no details on how teachers will be equipped to achieve these objectives. Mobile phones are to be banned in all schools, but qualifications are inevitable.

Scepticism about centralisation has been carried into specific areas. As a result, Te Pukenga, a single vocational education institution created from the merger of the country’s polytechnics and institutes of technology, will be disestablished. Other constraints on regional and local government autonomy will be lifted. But there is nothing to suggest that this ‘devolution’ will have a positive effect.

Centralisation is inextricably intertwined with the emotive issue of ‘co-governance’. It provides a vocabulary for contention over a wide range of issues relating to indigenous communities’ involvement in various areas of governance. But the question of how best to empower Maori people to participate in all aspects of New Zealand public life in a manner which satisfies Maori aspiration, while preserving aspects of culture valued by New Zealanders in common with many other societies, remains unanswered. Framing this challenge in terms of dubious assertions about an undefined ‘sovereignty’ will not help, nor will the belief that the events of 1840, when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, should determine current policy decisions.

As usual, foreign affairs played little role in the election. For advocates of change in New Zealand’s foreign policy positions — particularly towards a closer alignment with the United States and a greater focus on security issues relative to economic issues — Minister for Foreign Affairs Winston Peters’ first speeches will provide some comfort.

But there will be strong advocates for New Zealand to continue its avoidance of making uncomfortable choices. There may also be a reassertion of the importance of making independent decisions. While New Zealand will often support the United States, European Union and Australia due to their similar social institutions and historical relationships, the new government is very likely to diverge on some issues such as China’s role in international decisions.

Gary Hawke is Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and a member of the Academic Advisory Council of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA).

Source: East Asia Forum