New world, new hope: The struggle for a free western Sahara continues

Life under occupation is a constant struggle. This is continually expressed at the international media conference in a refugee camp in Western Sahara. The conference takes place from May 1–5 and is organized by the Sahrawi Union of Journalists and Writers (UPES).

Western Sahara is occupied by Morocco, a country where King Muhammad VI has full control over Morocco’s armed forces, judiciary, and all foreign policy. In Western Sahara, the Moroccan monarchy violates the human rights of the Sahrawi people. Children suffer from malnutrition, journalists are thrown in prison, and international observers are denied access to the occupied territories.

Morocco’s colonization of Western Sahara has been going on since 1975; however, the occupation receives little attention from the international community. Through the occupation, Morocco offers trade opportunities to Western companies while the Moroccan intelligence service uses Israeli spyware to monitor the Sahrawis.

But the revolutionary Sahrawi freedom movement—Polisario Front—is not giving up: In 2020, Polisario resumed its armed struggle against Morocco. The Sahrawis hope that a new world order, not dominated by the West, will open up new possibilities in the fight for a free and independent Western Sahara.

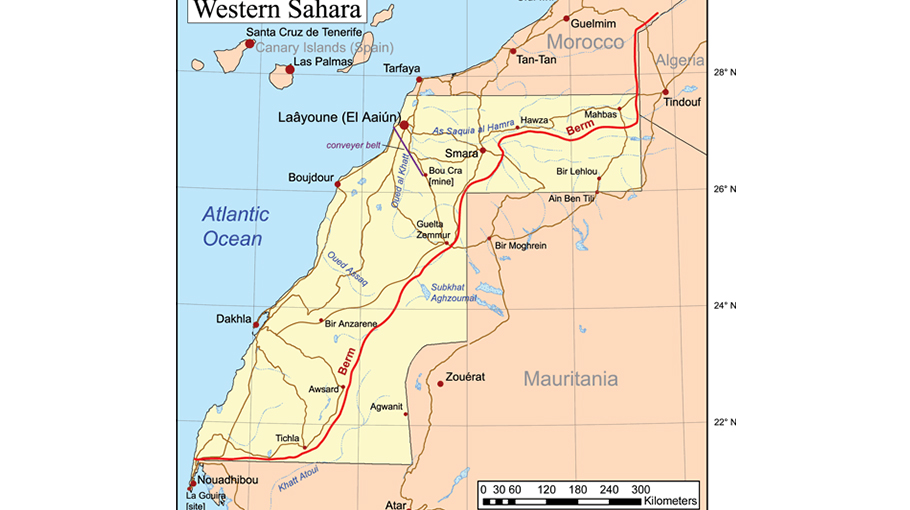

The media conference takes place in Wilayah of Bojador, one of five Sahrawi refugee camps located in Algeria on the border with Western Sahara. Algeria has given the area to Polisario, which administers the refugee camps. Thus, you could say that Western Sahara is divided into three areas. There are the occupied territories of Western Sahara, where Morocco is in power. There are the liberated areas of Western Sahara, where Polisario is in power. And then there are the refugee camps in Algeria, where Polisario is also in power.People may have traveled from all over the world to attend the media conference. However, it is the participants from the occupied territories of Western Sahara who receive the most acclaim at the opening of the various debates. This is due to the harsh living conditions in the occupied territories.

“Today, many children suffer from malnutrition due to the occupation,” says Buhubeini Yahya, head of the non-governmental organization (NGO) Sahrawi Red Crescent (SRC), which operates in the occupied territories. Problems with malnutrition are partly due to the fact that Morocco currently blocks Polisario’s access to the occupied territories, making the freedom movement unable to deliver humanitarian assistance to the local population. Sahrawi journalists—who want to cover malnutrition among children in the occupied territories, for example—are doing a job that can cost them dearly. Bhakha*, who works as a journalist in the territories, knows this.

“My colleagues and I are trying to expose Morocco’s crimes. But several have been arrested, some have received 27 years in prison,” Bhakha says from the stage. “Moroccan police kidnap journalists and confiscate our phones and cameras. Media people are having their bank accounts blocked and our websites are being cyberattacked,” he continues. Bhakha says that in the occupied territories, Morocco is cracking down on activists who organize demonstrations and speak out against the occupation. According to him, activists have been “thrown off tall buildings” as punishment for protesting.

“The Moroccan authorities have intensified their spate of violations against pro-independence Sahrawi activists through ill-treatment, arrests, detentions, and harassment in an attempt to silence or punish them,” the NGO Amnesty International wrote in 2021.

In eight months, Amnesty had recorded “seven cases of torture or other ill-treatment, three house raids, two de facto house arrests and nine cases of arrests, detentions and harassment of individuals in relation to their peaceful exercise of their freedom of expression and assembly.”

Sukina can’t hold back the tears. She is attending the media conference to talk about her brother Hussein, an activist from the occupied territories who has been thrown in prison for speaking out in favor of independence for Western Sahara. “I find it very difficult to talk about how much my brother is suffering in prison,” says Sukina.

Next to Sukina is journalist Mustaffa, who himself was locked up in a Moroccan prison as a political prisoner because he reported on the Moroccan occupation. Mustaffa describes a harsh prison system where inmates live in “miserable conditions” with many diseases circulating.

According to Prison Insider, a prison information platform, human rights organizations are concerned about Morocco’s “massive use of torture and ill-treatment of prisoners in Morocco and Western Sahara, where political prisoners are numerous and are particularly vulnerable.”

Sukina says that her family has to go through a lot to even see her brother Hussein in the Moroccan prison where he is being held. Just getting to the prison can take more than a day.

“The prison is many kilometers away from my family’s home. We have been forced to walk so far that my mother is now suffering from a kidney disease. There is nowhere near the prison where we can stay overnight. We have to go back and forth on the same day,” she says. Sukina continues, “Once we get there, it is not at all certain that the Moroccan prison guards will even let us see my brother. They have rejected us several times with mocking remarks.”

“And when they do let us meet with Hussein, it is always too short a meeting [and] under the supervision of the prison guards. My brother is not allowed to say a word about the conditions in the prison,” Sukina sighs. At the media conference in the refugee camp, many local participants express frustration that the international community generally turns a blind eye to Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara.

According to several experts on stage, the lack of focus is due to Morocco offering Western companies access to natural resources and other commercial opportunities in the occupied territories. Here, European companies are involved—through imports, exports, or the provision of technical services—in phosphate mining, wind power projects, agriculture, and fishing.

The economic exploitation of Western Sahara without the consent of the Sahrawi people is in violation of international law. The Sahrawis have not accepted the economic activities in the occupied territories and do not receive a share of the profits.

In 2017, the Danish shipping companies Ultrabulk and Clipper were caught in a political crossfire when it emerged that the shipping companies were shipping cargo from occupied Western Sahara. Anders Samuelsen, then the Danish foreign minister from the neoliberal party Liberal Alliance, refused to intervene.

In this way, Western companies and governments are helping to maintain the Moroccan occupation of Western Sahara. During the conference, there are repeated expressions of support for the Palestinians who are currently suffering from Israel’s genocide. All participants stand up and observe a minute of silence in solidarity with Palestine. In this way, one occupied people shows solidarity with another. The Sahrawis and the Palestinians are fighting against their respective occupying powers, who are collaborating with each other.

In December 2020, a month before his presidential term expired, Donald Trump declared that the United States now considered all of Western Sahara to be part of Moroccan territory. This is one of the decisions that current U.S. President Joe Biden has chosen not to change. In exchange for the declaration, the United States demanded that Morocco establish diplomatic relations with Israel. Today, Morocco recognizes Israel as a state and Israel recognizes Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Marc B. Sanganee is

editor-in-chief of Arbejderen, an online newspaper in Denmark.

Source: CounterPunch