New effort towards peaceful resolution of Afghan imbroglio

Both Parties- the United States and the Taliban-, after one week of relative peace and reduction in violence across Afghanistan, have signed a more comprehensive agreement on February 29 in Doha, Qatar.

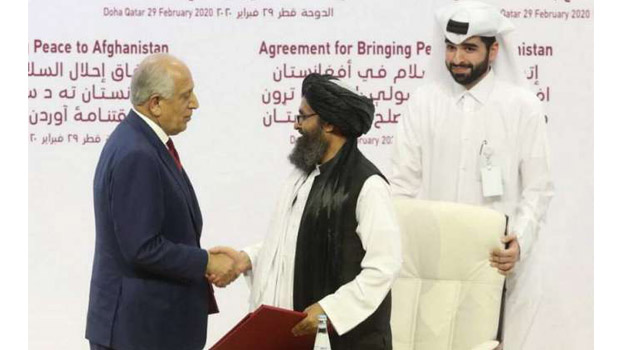

This has opened up the road to peace after nearly two decades of conflict. This has emerged after more than a year of talks between American and Afghan Taliban representatives. The agreement was signed by Zalmay Khalilzad, US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation and Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. The Afghan government, which has still been grappling with the dispute over the final results of that country’s latest Presidential election, was not part of the negotiations.

The current move is nevertheless being seen as an opportunity for the Taliban's leadership to show that they can control their fighters on the ground. It is also being seen as an opportunity that might pave the way for talks between Taliban negotiators and the different groups of Afghan politicians in that country.

It may be mentioned here that the US is hoping that this latest dynamics and a possible peace deal would help execute President Donald Trump's desire to withdraw US troops from Afghanistan. The first step is expected to reduce the current level of troops from 12-13,000 to 8,600.

It may be recalled that the US has spent billions of US Dollars since 2001 fighting the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan. This led President Donald Trump to pledge during his 2016 presidential campaign that he would end the US involvement in the war in Afghanistan and would take necessary steps for the withdrawal of US troops from the country.

It may also be mentioned here that the US-led invasion had driven the hardline Taliban from power in 2001, as part of a crackdown on Islamist militants after the 9/11 attacks in the US. Tens of thousand NATO troops were deployed and a long, bloody conflict followed as the ousted militants fought back. In 2014, NATO formally ended their combat mission, handing over this responsibility to Afghan forces, which it had trained. This process has however not worked satisfactorily. Since then, the Taliban have made substantial territorial gains across the country.

It may also be added here that contrary to claims by the Afghan government and its supporters among NATO Member States, the security situation within that country is not only becoming more complex but also creating anxiety within organizations associated with human rights. Inter-party disagreements and efforts to gain greater power through armed attacks on civilians as well as Afghan law and order personnel are making things rather uncertain.

Qatar has been hosting the talks between the US and Taliban leaders (who had moved there to discuss peace in Afghanistan) since 2011. It has been a difficult process. The Taliban, for this purpose opened an Office in Qatar in 2013 but closed it again later that year amid rows over flags. Other attempts at talks between the two Parties also stalled because of different factors at other times.

The evolving situation gained momentum in 2018 when Washington's top negotiator announced in September, 2018 that the US would withdraw 5,400 troops from Afghanistan within 20 weeks as part of a deal agreed "in principle" with Taliban militants. However, days later, Mr Trump said the talks were "dead", after the militant group admitted to killing a US soldier. He termed this as "a big mistake".

Subsequently, in December 2018, the Taliban announced that they would meet US officials to try to find a "road map to peace". However, the militants continued to refuse to hold official talks with the Afghan government, whom they dismissed as American "puppets". Despite this imbroglio, Qatar continued to play a pro-active positive role by arranging and hosting another major peace effort in July 2019. Afghan government officials attended sections of this meeting in their "personal capacity".

The Taliban, it may be pointed out, has been continuing to gain momentum within the Afghan paradigm. Recent reports have indicated that Taliban militants are active across 70% of Afghanistan. It may also be noted that nearly 3,500 members of the international coalition forces have died in Afghanistan since the 2001 invasion, more than 2,300 of them American. The figures for Afghan civilians, militants and government forces would be more difficult to quantify but a report prepared in February 2019 by the UN indicated that more than 32,000 civilians had died in Afghanistan. The Watson Institute at Brown University has however stated that 58,000 security personnel and 42,000 opposition combatants have been killed in Afghanistan.

It would be pertinent at this point to note that the Taliban have not been the only source of fanaticism and opposition in Afghanistan. Fundamentalist and radical elements in that country also include the presence of Al-Qaeda and Islamic State elements.

The Taliban, or "students" in the Pashto language, emerged in the chaos that followed the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989. They occupied Kabul in 1996 and were in charge of most of the country within two years, practicing their own austere version of Sharia, or Islamic law. This included- banning TV, music and cinema, enforcing strict dress codes, severely curtailing female education and also introducing brutal punishments. Mullah Omar continued to lead the Taliban after they were ousted from power in Kabul. He died in 2013. The Taliban are now led by Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada.

It appears that Washington's longest ever war could be coming to an end, and President Donald Trump - in a crucial re-election battle year - may be able to make good on his promise to bring a substantial number of US troops back home. Observers have consequently noted that the stakes for the Trump administration and also for the US are high.

However, as noted by Jonathan Marcus, the stakes for Afghanistan are even higher. The very political future of that country is at stake. Many observers are also asking the question as to what form or system of government will exist in that country.

The New York Times has identified an important aspect. They have pointed out that “the next stage of talks (that are expected to be initiated from the second week of March) could easily consume a year or more. They will have to tackle much thornier questions of how to share power and security responsibilities and how to modify State structures in satisfying both the government’s interest in maintaining the current system and the Taliban’s interest in something they would regard as more Islamic.”

It is as such being felt by geo-strategic analysts that both sides will need to generate traction in intra-Afghan negotiations, without getting distracted by those who might seek to capitalize on the fragility of the status “reduction in violence” pledge or any cease-fire agreements that might follow.

Despite hope and optimism it is also clear that there are other terrorist and fundamentalist stake-holders operating in the rural areas of Afghanistan and they might not agree to cooperate with the evolving dynamics. There might be lesser number of attacks on major cities and highways- but there, in all probability will be continued violence in several other parts of the Afghan landscape. The Taliban appear to have however agreed not to host, train or carry out fundraising operations in the areas that they control.

On the other hand, one also needs to take note of the comments made by US Defence Secretary Mark Esper with regard to US troop’s withdrawal and the talks with the Taliban. He has affirmed that "a significant part of our operations" in Afghanistan would be suspended, but added that the "clock has not yet begun" and that further consultations were needed to settle some other issues like future US involvement in training of the Afghan armed forces.

This deal now opens the door to separate, wider talks between the militants and other Afghan political leaders - including government figures. There is cautious optimism but analysts have also been pointing out the difficulties that could be created because of the ongoing political dispute over the results of the Afghan presidential election - with Ashraf Ghani's rival Abdullah Abdullah alleging fraud. A backdrop of political instability could make it harder to establish the "inclusive" negotiating team international observers want to see sitting across the table from the Taliban.

Up until now, the Taliban have been, perhaps deliberately, vague. There are possible obstacles even before those talks begin. The Taliban do however appear to want international legitimacy and recognition and also release of 5,000 of their prisoners. On the other hand the Afghan government wants to use those detainees as a bargaining chip in the talks to persuade the Taliban to agree to a ceasefire. It has already been underlined by Ashraf Ghani that such release of prisoners cannot be a pre-condition for talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government.

The situation is still very delicate. Despite efforts between Trump and Taliban leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, dozens of incidents have already taken place in the first week of March in more than 16 Afghan provinces that left eight militants and six civilians dead. Eight security personnel have also been killed.

It is also not clear as to where Pakistan stands on this issue and whether there will be wider regional framing for any final settlement. We also do not know how the Taliban will respond to NATO continuing to have any responsibility in terms of creating and maintaining governing institutions required for future stability and good governance in Afghanistan?

One needs to conclude here by referring to an interesting observation made by veteran US defence expert Tony Cordesman. He has raised concerns that the "peace" being sought by President Trump might rather be the "Vietnamisation" of a US withdrawal. According to him " this peace effort may actually be an attempt to provide the same kind of political cover for a US withdrawal as the peace settlement the US negotiated in Vietnam" more than four decades ago.

Muhammad Zamir, a former Ambassador, is an analyst specialized in foreign affairs, right to information and good governance