Lenin and October Revolution

The October Revolution in the Soviet Russia under the leadership of Vladimir I Lenin took place at a time when all over the world the working class suffered in the hands of brutal regimes who believed in making profit only. Human rights and work ethics were of no value to them. Thousands of workers perished the gold, copper and iron ore mines while others died in dark and damp factories.

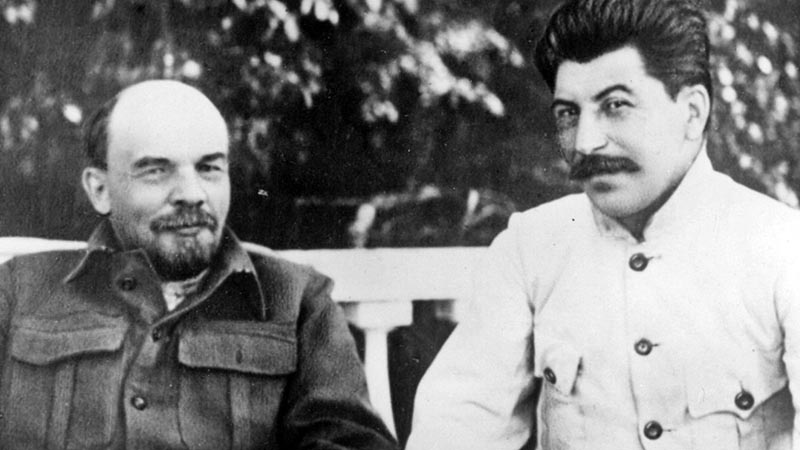

In Russia, ruled by a tyrant Zar, workers had no fixed work hours, no union to voice their grievances and no hope of getting justice from Zar’s justice system. The Bolshevik party took the vow to wage guerrilla warfare to oust the Zar and his henchmen and establish rule of law. They organized under Lenin, Stalin, Trotskyand other young leaders in the distant mountains. They finally attacked the Zar’s palace and arrested him along with his family. This came to be known as October Revolution of 1917.

Lenin showed the beacon of light to the working people of the world who also organized to form communist party in every corner of the world. Thus, Lenin became the iconic leader of the down-trodden and poor working class of people. Here we pay tribute to this great people’s leader of all time.

Vladimir Lenin, also called Vladimir Ilich Lenin, original name Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov, founder of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), inspirer and leader of the Bolshevik Revolution (1917), and the architect, builder, and first head (1917–24) of the Soviet state. He was the founder of the organization known as Comintern (Communist International) and the posthumous source of “Leninism,” the doctrine codified and conjoined with Karl Marx’s works by Lenin’s successors to form Marxism-Leninism, which became the Communist worldview.

If the Bolshevik Revolution is—as some people have called it—the most significant political event of the 20th century, then Lenin must for good or ill be regarded as the century’s most significant political leader. Not only in the scholarly circles of the former Soviet Union but even among many non-Communist scholars, he has been regarded as both the greatest revolutionary leader and revolutionary statesman in history, as well as the greatest revolutionary thinker since Marx.

As an adolescent Lenin suffered two blows that unquestionably influenced his subsequent decision to take the path of revolution. First, his father was threatened shortly before his untimely death with premature retirement by a reactionary government that had grown fearful of the spread of public education. Second, in 1887 his beloved eldest brother, Aleksandr, a student at the University of St.

Petersburg (later renamed Leningrad State University), was hanged for conspiring with a revolutionary terrorist group that plotted to assassinate Emperor Alexander III. Suddenly, at age 17, Lenin became the male head of the family, which was now stigmatized as having reared a “state criminal.”

In autumn 1887 Lenin enrolled in the faculty of law of the imperial Kazan University (later renamed Kazan [V.I. Lenin] State University), but within three months he was expelled from the school, having been accused of participating in an illegal student assembly. He was arrested and banished from Kazan to his grandfather’s estate in the village of Kokushkino, where his older sister Anna had already been ordered by the police to reside. In the autumn of 1888, the authorities permitted him to return to Kazan but denied him readmission to the university. During this period of enforced idleness, he met exiled revolutionaries of the older generation and avidly read revolutionary political literature, especially Marx’s Das Kapital. He became a Marxist in January 1889.

The principal obstacle to the acceptance of Marxism by many of the Russian intelligentsia was their adherence to the widespread belief of the Populists (Russian pre-Marxist radicals) that Marxism was inapplicable to peasant Russia, in which a proletariat (an industrial working class) was almost nonexistent. Russia, they believed, was immune to capitalism, owing to the circumstances of joint ownership of peasant land by the village commune. This view had been first attacked by Plekhanov in the 1880s. Plekhanov had argued that Russia had already entered the capitalist stage, looking for evidence to the rapid growth of industry.

In an attack on the Populists published in 1894, Lenin charged that, even if they realized their fondest dream and divided all the land among the peasant communes, the result would not be Socialism but rather capitalism spawned by a free market in agricultural produce. The “Socialism” put forth by the Populists would in practice favour the development of small-scale capitalism; hence the Populists were not Socialists but “petty bourgeois democrats.” Lenin came to the conclusion that outside of Marxism, which aimed ultimately to abolish the market system as well as the private ownership of the means of production, there could be no Socialism.

In his What Is To Be Done? (1902), Lenin totally rejected the standpoint that the proletariat was being driven spontaneously to revolutionary Socialism by capitalism and that the party’s role should be to merely coordinate the struggle of the proletariat’s diverse sections on a national and international scale. Capitalism, he contended, predisposed the workers to the acceptance of Socialism but did not spontaneously make them conscious Socialists.

The differences between Lenin and the Mensheviks became sharper in the Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath, when Lenin moved to a distinctly original view on two issues: class alignments in the revolution and the character of the post-revolutionary regime. The outbreak of the revolution, in January 1905, found Lenin abroad in Switzerland, and he did not return to Russia until November. Immediately Lenin set down a novel strategy. Both wings of the RSDWP, Bolshevik and Menshevik, adhered to Plekhanov’s view of the revolution in two stages: first, a bourgeois revolution; second, a proletarian revolution (see above).

After the defeat of the Revolution of 1905, the issue between Lenin and the Mensheviks was more clearly drawn than ever, despite efforts at reunion. But, forced again into exile from 1907 to 1917, Lenin found serious challenges to his policies not only from the Mensheviks but within his own faction as well.

Dramatizing his break with the reformist Second International, in 1918 he had changed the name of the RSDWP to the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), and in March 1919 he founded the Communist, or Third, International. This International accepted the affiliation only of parties that accepted its decisions as binding, imposed iron discipline, and made a clean break with the Second International. In sum, Lenin now held up the Russian Communist Party, the only party that had made a successful revolution, as the model for Communist parties in all countries.