Japan and China’s economies are adapting, not decoupling

Japan is one of the countries most affected by geopolitical competition between the United States and China. Although the economies of Japan and China seem to be on the first track of economic decoupling in many ways as a result, they are actually only experiencing a period of structural economic change.

Contrary to the prevailing perception, Japanese initiative, not the US–China rivalry, is driving the structural shifts in Japan’s economic security policy. China’s abrupt restrictions on rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 amid a dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands were a wake-up call for Japan, and since then, Japan has been working to reduce its overdependence on China.

In 2020, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry introduced measures to help Japanese companies shift production from China to Southeast Asia or Japan.

The Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) now administers the Subsidy for Projects to Stimulate Direct Investment in Japan.

The Japanese government has now specified critical products and raw materials that are essential to daily life and economic activities.

Japan enacted a far-reaching Economic Security Law in May 2022, providing a legal basis for economic security policy and clarifying Japan’s understanding of economic security. Under this law, Japan aligned its policy with the United States and the Netherlands by tightening export restrictions on technologies related to semiconductors and quantum computing. Although one potential explanation for this move was the United States’ extraterritorial unilateral sanctions, which gave Japan little choice in their policy alignment, a more convincing reason is that there were fears that such technology could be diverted for military purposes once China had access to. That same year, China’s share of Japan’s imports and exports was 20 per cent, which may indicate a downward trend as Japan’s main exports to China are products related to the semiconductor industry.

Like many global companies doing business

with China, Japanese companies have undergone

a significant shift in the way they formulate their

business strategies since the war in Ukraine

Recent news has reinforced the image of decoupling between the Japanese and Chinese economies. Following Mitsubishi Motors’ withdrawal from China, Honda plans to reduce its manufacturing workforce in China. These are the latest examples of a trend stemming from the rising labour costs and fierce competition from Chinese rivals that have characterised the last decade. Given that only 60–70 per cent of Japanese companies are profitable in China, falling profit margins have led to the gradual withdrawal of 30–40 per cent of companies from China.

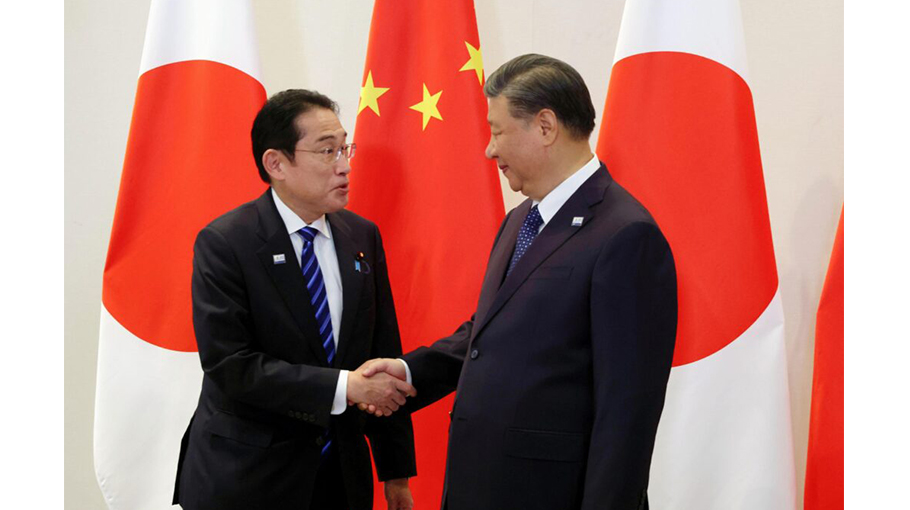

Despite appearances, these trends reflect the dramatic structural change facing the economies of Japan and China, not decoupling. The Asia-Pacific is an anti-globalist exception, still moving towards regional economic integration. The Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership entered into force in 2018 and 2022 respectively. Japan, China and South Korea agreed to resume negotiations on a trilateral free trade agreement at a summit in May 2024. This is a clear signal from the leaders of the three major powers in the region that economic relations are vital and must continue.

The goal of the Japanese government’s economic security initiative is to construct a ‘small yard, high fence’. Among the 87 companies that received government subsidies in June 2020, most manufacture strategic assets such as aviation parts and medical equipment. As such, JETRO’s projects are only for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Most importantly, Japanese companies are adapting their way of doing business, and most of them are not leaving China. Faced with challenges such as rising labour costs and strained political relations between Japan and China, Japanese companies started to adopt a ‘China Plus One’ strategy in the early 2010s, shifting some of their business to ASEAN countries. In response to supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, many Japanese companies adopted a ‘China for China’ strategy.

Like many global companies doing business with China, Japanese companies have undergone a significant shift in the way they formulate their business strategies since the war in Ukraine. Geopolitical considerations have now taken precedence over macroeconomic forecasts. This shift in Japanese companies’ thinking has reinforced the ‘China for China’ strategy that these companies have in place.

New technology has also created a new business model for trade between Japan and China — e-commerce. In 2022 alone, Chinese consumers have purchased US$14.4 billion worth of Japanese products through e-commerce.

The economic interdependence that has been a key feature of the Japan–China relationship may not be easily broken. As of 2023, China is still Japan’s largest trading partner and Japan is China’s second-largest trading partner after the United States. In a region where the trend towards economic integration is continuing, political leaders show a strong intention to stabilise economic relations, and economic security policy does not aim at full decoupling.

In the process of adapting to geopolitical challenges, Japanese companies are taking the lead in changing the dynamics of the economic structure between Japan and China.

Rumi Aoyama is Professor in the Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies and Director of the Waseda Institute of Contemporary Chinese Studies at Waseda University.

Source: East Asia Forum