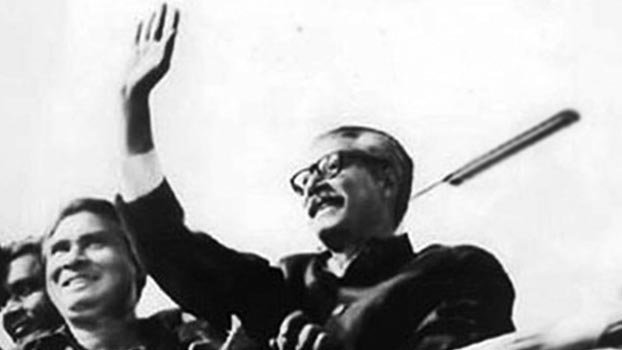

Bangabandhu comes home

A moment to achieve completeness of liberation war

Forty eight years ago today, a thankful Bangalee nation welcomed the Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman back home. His homecoming was for all of us the breaking of a new dawn in our lives. It brought a moment for the nine month long War of Liberation to achieve completeness. Bangabandhu came back after nearly ten months of imprisonment in Pakistan. In those months the people of Bangabandhu, in his name, successfully waged an epic battle to free the country of the prowling Pakistan occupation forces which had left three million people dead, two hundred thousand women raped and countless villages and towns plundered and damaged.

Since the late 1940s, Bangabandhu had never been a stranger to prison as the Pakistan state incarcerated him every now and then. But during war of liberation, his imprisonment was a harsher experience for it was for the first time he had been lodged in prison away from his land and in an unknown terrain of Mianwali in Pakistan. Worse was it that he had been allowed to access to newspapers, radio and television. Thus he had been put in complete darkness about what was actually happening in his country and to his people, and what the international community had been thinking about the war of the Bangalee people.

The military regime of General Yahya Khan, having repudiated the results of an election that not only acknowledged Bangabandhu as the undisputed leader of the Bangalee nation but also the incoming prime minister of Pakistan, was clearly determined to put its prisoner out of the way by placing him on trial before a secret military tribunal. The case failed with the collapse of the Pakistan army in Bangladesh in December 1971 though.

Today, all these decades after Bangabandhu’s return home and nearly forty three years after his cruel assassination, a very pertinent question comes up regarding the conspiracy which felled him. Those who murdered him and his family and later the four national leaders in prison quickly made clear their political orientation coming back with ‘zindabad’ politics, in the old Pakistani style, and reintroduced communalism in the national narrative. The frenzy with which the votaries of a so-called Bangladeshi nationalism have consistently launched assaults on secular politics, the audacity with which they have been trying to storm back to power are all a recurrent message to us that vigilance is yet very much a national need. Our remembrance of Bangabandhu will achieve meaning when we can restore his philosophy and have it permeate all levels of consciousness in our society.